Karmadon Viscous Damped Unipivot Tonearm and Miyajima Laboratories Spirit Mono Phono Cartridge

Party Like It’s 1949

Let’s face it. Despite some really extravagant advertising copy a turntable is just a wheel. And while we consistently see small incremental improvements in materials and manufacturing tolerances, particularly since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the mid eighteenth century, we’ve had the basics down for around five thousand years or so. A flat round thing attached to a stick of some sort.

Let’s face it. Despite some really extravagant advertising copy a turntable is just a wheel. And while we consistently see small incremental improvements in materials and manufacturing tolerances, particularly since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the mid eighteenth century, we’ve had the basics down for around five thousand years or so. A flat round thing attached to a stick of some sort.

In a recent article I droned on in minutia about the build qualities and restoration process of the ancient Rek-O-Kut T12h idler drive turntable that’s now doing duty for mono records downstairs in my cave. As consumer electronics go this thing is ancient, built somewhere between 1948 and 1955, well before any of the computerization that allows for the nano-tolerances that can be achieved in today’s machine work. My overall conclusion: The T12h can’t hold a candle to today’s turntables for speed stability or overall precision, but it nevertheless sounds pretty darned good. It’s also a battleship: massively built almost entirely from milled aluminum without a nip of plastic or a circuit board in sight. Nobody builds turntables like this anymore. Come to think of it, nobody really builds anything like this any more.

I started with an ancient machine with no arm, arm board, cartridge or plinth, and had the opportunity to put together a complete turntable in whatever way I felt would best compliment sixty-year-old vinyl. There’s almost nothing on the market today that requires the user to create the rest of the component around the naked mechanicals. (The one exception that comes to mind is the newly re-released version of the Technics SP-10, which I’d love to have a crack at). I’m no engineer and this is the first time I’ve ever done a project like this but when it was finished I had a running turntable, and believe me, that was a minor miracle in and of itself.

It’s not perfect, of course, at least not by today’s standards. The biggest sonic deficiency is speed stability – sometimes referred to as WOW – an issue I’m still working through, which is ironic because the T12h was originally marketed as one of the first turntables to meet the National Association of Broadcaster’s standards for that measurement.

It’s not perfect, of course, at least not by today’s standards. The biggest sonic deficiency is speed stability – sometimes referred to as WOW – an issue I’m still working through, which is ironic because the T12h was originally marketed as one of the first turntables to meet the National Association of Broadcaster’s standards for that measurement.

Careful setup goes reasonably far towards lessoning this effect. For example, keeping the platter and main bearing assembly absolutely, painstakingly level – which you should do anyway – and therefore keeping the motor as close to perpendicular as possible, reduces the modulation, but not entirely. The effect also seems to be decreasing simply with time as the grommets settle in a little, but I’m also looking for ways to lock the motor into a more stable position when running, though this may require a new plinth.

Of course, I could also be barking up the wrong tree entirely, and this theory could change completely by next week.

All of that notwithstanding, I’m really enjoying using and listening to the T12h, though it certainly requires an adjusted set of expectations. I don’t pull my hair out worrying whether it’s as refined or precise as my Sota, because it’s not. It’s a seventy-year-old turntable seemingly built as much for military durability – a good description of it – over anything close to what we’d consider to be today’s mechanical precision. With that understanding I can just listen to it and enjoy it.

The Rek-O-Kut T12h sounds far better than you might think based on the description I’ve just offered. Monaural records – which is all there was when this thing was built – sound great. Not perfect by today’s high-fidelity standards, but still great. I listen to it at least as much as I do to my stereo Sota, and often more so. The monaural sonic image is large, and the sound is colorful and dynamic.

A great deal of this success is surely due to what turned out to be prescient choices in associated turntable components, which leads to the subjects of this review. Installed on the table are two somewhat unusual subordinate pieces: the Karmadon twelve-inch Viscous Damped Unipivot Tonearm and the Miyajima Spirit Mono cartridge. Both are very much in the tradition of vintage designs and both proved to be a good sonic and aesthetic match for the T12h.

Beer and Cartridges

Prior to getting the T12h up and running I was using a grungy, badly oxidized Mark-I Technics 1200 for my mono listening. The Tech-12 began with a Grado monaural cartridge, which was a pretty good starter combo, but only briefly before I ham-handedly destroyed the cartridge. The dead Grado was quickly replaced with an Ortofon 2M Mono which also sounded quite nice (and has threaded mounting holes, hint, hint…). Both cartridges have some good qualities for what they are: competent entry-level moving-magnet monaural cartridges. Both are affordable and easy to recommend.

Last November at Capital Audiofest, Robyn Wyatt of Robyatt Audio was pitching the line of Miyajima cartridges, which he imports, accompanied with free beer, which may have greased what came next. With no premeditation whatsoever (I swear), I plopped down my Visa card for a brand new Miyajima Spirit Mono cartridge, a big step up from the relatively mass-market Grado and Ortofon pickups to a more specialized bit of Japanese analog exotica.

By this time, I already had the unrestored mechanical portion of the T12h in a box in the garage. The rapidly crystalizing plan now included the Spirit Mono as a key component of what would be a newly assembled vintage turntable to replace the Tech-12 for monaural listening.

Another important component of this plan involved buying a fancy new sewing machine for my wife a few weeks later, but that’s another story altogether.

The Miyajima Spirit Mono Cartridge

The Spirit Mono is the first step-up model in Miyajima’s line of five monaural cartridges. It’s a moving coil with .7mV output and 6 Ohms impedance. A high-output version with 3.7mV is also available. It’s moderately weighted at 10 grams and is designed to track at a comparatively high 2 – 4.5 grams with 3.5 grams recommended. The sides of the cartridge body are brass with ‘Spirit’ engraved in them, and what appears to be a piece of black acrylic sandwiched between them. Mine has a conical stylus which Miyajima has since replaced with an elliptical stylus for improved tracking. I’ve never experienced any tracking issues with the older version unless there was a problem with the vinyl.

Many monaural cartridges, like the Ortofon that I’d been using, are stereo pickups that are strapped for mono output. There are still four coils inside body collecting the signals from the grooves in both the lateral and vertical planes. The signature feature of the Spirit – and all of the Miyajima mono cartridges – is that they’re true monaural designs, built the way mono cartridges were built before the advent of stereo: two coils picking up the signal as the stylus modulates horizontally, with no vertical compliance at all. The theoretical advantage of this is that the cartridge doesn’t pick up additional noise from the parts of the groove that were never intended to be heard in the first place and should therefore be quieter. In fairness to both the Grado and Ortofon cartridges, they were both quieter on mono records than their stereo counterparts, but the Spirit, with just the two coils, is quieter still. The cartridge does, however, have the standard four color-coded pins on the back so it connects to a tonearm like any other cartridge.

Many monaural cartridges, like the Ortofon that I’d been using, are stereo pickups that are strapped for mono output. There are still four coils inside body collecting the signals from the grooves in both the lateral and vertical planes. The signature feature of the Spirit – and all of the Miyajima mono cartridges – is that they’re true monaural designs, built the way mono cartridges were built before the advent of stereo: two coils picking up the signal as the stylus modulates horizontally, with no vertical compliance at all. The theoretical advantage of this is that the cartridge doesn’t pick up additional noise from the parts of the groove that were never intended to be heard in the first place and should therefore be quieter. In fairness to both the Grado and Ortofon cartridges, they were both quieter on mono records than their stereo counterparts, but the Spirit, with just the two coils, is quieter still. The cartridge does, however, have the standard four color-coded pins on the back so it connects to a tonearm like any other cartridge.

Also similar to those vintage cartridges, the Spirit has a very large cantilever made of what appears to be a folded metal tube. Compared to the hair-thin, barely visible, and obviously delicate cantilever in the Audio-Technica AT33Sa currently riding in my Sota (review forthcoming), the Spirit’s cantilever is a far more robust piece.

That robust construction turns out to have a very practical advantage. I have occasionally encountered a record where the run-out groove hadn’t been pressed deeply enough, allowing the cartridge and arm to jump out of the trailing groove and over the paper label at the end of the side. In one particularly egregious incident shortly after I installed it, an early copy of Thelonious Monk’s Brilliant Corners turned the Spirit’s cantilever sideways at a grotesque almost 90-degree angle from center that would have signaled the death of almost any other cartridge. Believe me, having just purchased it, this was a scary moment when it happened.

That robust construction turns out to have a very practical advantage. I have occasionally encountered a record where the run-out groove hadn’t been pressed deeply enough, allowing the cartridge and arm to jump out of the trailing groove and over the paper label at the end of the side. In one particularly egregious incident shortly after I installed it, an early copy of Thelonious Monk’s Brilliant Corners turned the Spirit’s cantilever sideways at a grotesque almost 90-degree angle from center that would have signaled the death of almost any other cartridge. Believe me, having just purchased it, this was a scary moment when it happened.

Fortunately, the Spirit wasn’t quite ready to give up the ghost (no pun intended). Instead of calling for last rites, all that was required to fix it was to gently but firmly push the cantilever back to the center position with my finger and then throw on another record. In fact, those are Miyajima’s instructions, which are printed on a separate piece of paper complete with photographs in the packaging. I would not have believed it if I hadn’t performed the procedure myself. It’s obviously not a trick I want to repeat on a regular basis, but I’m damn glad the trick can be done if necessary. On a turntable that’s built like a battleship I also managed to find a cartridge that’s built like a tank.

Another noteworthy feature is how powerful the magnets are. Several times while mounting it the magnets forcefully plastered the cartridge body to my pair of needle-nose pliers – hence the fine scratches in the picture – something I’d never experienced with any other cartridge. With no threaded mounting holes – C’mon guys, it’s 2018 – it made getting the tiny nuts affixed a bit of challenge, but once they were on it was no different than adjusting any other cartridge. There is, in fact, a warning about this magnetic effect in the manual, but somehow I’d missed that part when I was installing the cartridge (I don’t need no stinkin’ directions!).

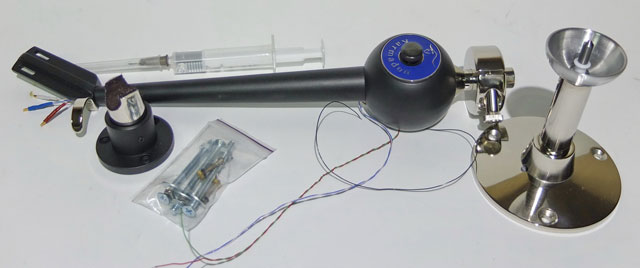

The Karmadon Viscous Damped Unipivot Tonearm

I first got wind of the Karmadon tonearms through some of the hi-fi message boards discussing old turntable restorations and mono setups. The arms have garnered a small but enthusiastic following among the vintage crowd. At the time, I was considering a Gray Research 108 or one of its myriad clones for the T12h. the Karmadon arms are heavily based on those earlier Gray designs, so after a bit of research and a few emails I was intrigued enough to want to try one.

At first glance, mail ordering an un-reviewed tonearm from a former Soviet republic with little information other than the peanut-gallery opinions on a few message boards might seem like a risky proposition – after all, there is no U.S. distributer – but there was a big compensating factor: the Karmadon Unipivot is incredibly affordable. On a five-thousand-dollar component I want someone else to try it and write a review before I put my money on the counter. At a mere $420 – you read that right, $420 US – I was willing to take that risk myself. A small manufacturing shop in the Ukraine seems an unlikely place to find a tonearm, but we live in an interconnected world, so why not? Communication with Mr. Rogoziansky via email has been very good.

Serge Rogoziansky, who describes himself as a mechanic by training with a longtime interest in electronics, started his business doing restorations on vintage equipment about fifteen years ago, primarily old idler drive turntables but also some tube amps and horns. A gallery on his website shows his handiwork on a variety of well turned out Byers, Rek-O-Kut, RCA, Metzger-Starlight and other vintage tables. In the service of those restorations he can also re-fabricate parts as necessary.

As he tells it, somewhere along the way he had a vintage Gray Research 108 arm in his shop, was impressed with its sound, and decided to clone it using the same needle and cup style unipivot with a fixed counterweight and head-shell. On the original Gray 108 the counterweight was a non-adjustable slug of lead. Setting VTF was a matter of adding small brass plates directly over the cartridge until the desired tracking force was achieved, the assumption being that the counterweight would be heavier than any cartridge so loading weights onto the front end was necessary to get the needle to make contact with the record. This is quite the opposite of virtually all other modern tonearms where the weight adjustment is applied entirely behind the arm’s fulcrum. Rogoziansky’s 108 clone requires the same front loading as the original. He continues to sell his 108 clone in both 9” and 12” versions, and people who like them seem to really like them, but he also felt that he could improve upon the concept.

Rogoziansky’s own design – the co-subject of this review – utilizes the same geometry and bearing type as his 108 clone, but with the modern flexibility of an adjustable rear-mounted counterweight and a slotted head-shell for more precise alignment. This provides for all the standard adjustments most consumers expect in a tonearm, albeit in a very basic way. This design is cast from solid magnesium alloy, which was chosen for its resonance properties, and like the earlier effort is also available in 9” and 12” versions.

The first thing that stands out about this arm is how heavy it is. The arm and pivot body – which appears to be a single casting – is a long, tapered shaft with an integral, slotted, fixed-angle head-shell at one end and a large hollow ball, a little bigger than a squash ball, at the other. The shaft itself is not merely a thin hollow pipe as found on many tonearms. It’s solid cast metal with a small hole bored through it for the wires. It’s a hefty piece. The arm was intended to be a high-mass design, and indeed there is a lot of metal here. A chromed post protruding from the back of the pivot ball supports the counterweight.

Inside the hollow pivot body is an inverted split half-dome with a small adjustable steel cup in the top. On the base shaft there is a pin sticking straight up from a bowl. The bowl receives the silicone damping fluid, and then the cup gets set on the pin. The split half dome floats in the silicone, providing the damping for the arm. Those bits all sit on top of a chromed mounting shaft, which is adjustable for height using a setscrew in the base. It’s an effective update to the system that was first used in the Gray Research arms some seven decades ago.

Most tonearms today have counterweights that are threaded in some way to allow the user to simply turn the weight to adjust the tracking-force. On this arm the counterweight, which is not threaded, is held in place with a finger-nut. Loosen the nut and slide the weight fore or aft along the shaft to set your desired VTF. This is not an unheard-of setup – some of the VPI arms work this way – but it’s not terribly common either. Getting an accurate tracking force in 100ths of a gram required a lot of very light taping to move the weight in miniscule increments, a time-consuming process that required some patience. The same weight also adjusts azimuth by rotating the counterweight to adjust the roll axis of the arm.

Neither of these controls are as easy to operate precisely as they would be on a big-buck arm, but this isn’t a big buck arm. It takes a little more effort, but with care during setup both adjustments are perfectly effective. Once adjusted there were no problems with slippage or any other unexplained setting migrations.

Another old-school feature is that there is no lever to raise or lower the tonearm onto the record, though Rogoziansky does make one that’s available separately through his website. I hadn’t used a tonearm without a lift since college when I worked in a radio station that still had a bunch of Sparta idlers in the booths. It wasn’t a big deal to lift a tonearm by hand in the early 1990s and I don’t find it to be a big deal today. The arm does, however, come with a suede-lined adjustable armrest.

There’s another unusual feature that anyone considering this arm needs to know upfront. The Viscous Damped Unipivot comes with excellent quality Cardas wire with cartridge clips in the head-shell, but as-delivered those wires aren’t connected to anything on the other end: no DIN clips, RCA jacks, or any other pre-installed connection points, just two feet of bare wire hanging out of the back of the tonearm. Unless you arrange to have Mr. Rogoziansky do some type of custom setup, which I understand he can do, you’ll need to either solder the wires into standard jacks of some sort or know someone who can do it for you. I chose to do it myself, but a cautionary note: The Cardas wire is incredibly fine – by some accounts finer than a human hair – and my eyes aren’t as good as they used to be. If you’ve ever read an article describing neat, perfectly applied dabs of solder, my soldering skills are the exact opposite of that: sloppy, misshapen blobs of silver all over the place. I spit a lot of four-letter words while soldering these connections. Make sure you’ve got plenty of good light and some form of strong magnifier. I was ultimately able to set up an operable output junction bolted to the back of my turntable – and for the record, it does not hum – but it’s not the most professional looking job you’ll ever see. Your results may vary.

There was one last surprise in the box. I’ve received silicone damping-fluid in syringes through the mail before, but this was the first time I’d ever received silicone in a syringe with the needle still attached, and a big two-inch needle at that. Knowing that U.S. Customs is theoretically tighter than it’s been in decades I was amazed that the syringe hadn’t been flagged for further scrutiny. Fortunately, no one was handcuffed at the post office which is a good thing because it was my wife who picked up the package. Boy, can you imagine how awkward that could have been?

If you’ve gotten the impression that this arm is a little unusual, you’d be correct. As shipped, it does without modern niceties like built-in spirit levels, threaded precision micro-adjustments for every parameter, or even connection jacks. It requires the user to have a few basic mechanical skills and some patience to set up, but the Karmadon Viscous Damped Unipivot is a very substantial tonearm: simple, cleanly cast and very nicely finished. There are no rough spots or obvious manufacturing shortcuts in evidence, it’s unbelievably affordable and, as we’ll get to in a few moments, it works really well. Lest anyone get a different impression, I am enthusiastic about this tonearm.

Nuts, Bolts, Wrenches and Screwdrivers

On the Rek-O-Kut, mounting the Karmadon arm was simple enough. A friend with access to a CNC machine had cut the brass swing-arm with three holes bored and threaded specifically to accept this arm. With the base and shaft installed, setting the arm in place required simply placing the damping fluid in the bowl and dropping the arm onto the pin. I’d already pre-soldered the loose wires to a pair of RCA jacks and a ground point which are all secured to a piece of Plexiglas now mounted to the back of the plinth.

Setting up the Spirit Mono was likewise pretty straightforward – the lack of threaded holes in the cartridge notwithstanding. I used a Dr. Fleikerts protractor to first determine the proper 270 mm spindle-to-pivot distance on the tonearm, adjusted the swing-arm accordingly, aligned the cartridge along the Bearwald marks, and tightened it all up. The table is connected to my Aurorasound SP-03h step-up transformer that in turn feeds the phono stage in my Cary SLP-98p preamp.

The first time I put a record on the platter, shifted the table into gear and dropped the needle I held my breath for a second. Then, music miraculously sprang forth from my speakers. I confess, I was probably more impressed with my effort than I should have been, but with my limited mechanical skills it was never a foregone conclusion that this table would work as intended, or even at all.

It sounds like…mono…

We talk about sound staging in analog: the ability of a turntable (or any source, really) to throw a realistic sonic image into the room. Stereo imaging is usually discussed in the context of the depth and breadth of the stage, speaker to speaker and sometimes beyond if the record is particularly well recorded.

We talk about sound staging in analog: the ability of a turntable (or any source, really) to throw a realistic sonic image into the room. Stereo imaging is usually discussed in the context of the depth and breadth of the stage, speaker to speaker and sometimes beyond if the record is particularly well recorded.

Mono is a different kettle of fish. There is a sonic image, of course, but it’s neatly arranged and centered between the speakers. That, however, is not the end of the story. Depending on the setup, width should still be achieved, and imaging can be considered in terms of stability and clarity. A great mono recording will be centered, but it should not sound like a thin, narrowly stacked, vertical band of music. It will have some fullness, width, and height, and the sonic image will be well defined, stable, and even palpable. Depth – the layering of instruments in the soundstage – is also often present, depending on the recording. Personally, I’ve been in plenty of venues where the musicians sound like this – emanating from a specific area, but not spread out laterally. There’s a case to be made that a mono recording may more realistically capture what you’d hear with your own ears in many live circumstances. Stereo recordings by contrast, can sometimes be the constructs of engineers, with instruments spread around to isolate them from each other in the sound stage, especially if the recording is multi-tracked in a studio. I’m generalizing, of course. Both formats can be sonically valid, but that validity can be dependent on the circumstances in which the recording was made.

The other thing about monaural records is that depending on the equipment that was used, the capture of the instruments can be every bit as good as it is on a stereo record, it’s just that those instruments will be arranged differently when they get to your ears. The technological leap between mono and stereo was in the second channel and spatial arranging, not the capability of microphones to capture the instruments or the tape to record it. Exceptionally good recording equipment – Neumann microphones, Ampex recorders, etc. – were around for a decade or more before two-channel playback became widespread in the market.

Mellow Gold

The Spirit Mono is a little like an older SPU: supremely musical with excellent weight and depth, but without that high treble air and sparkle that you get out of some modern moving coils. That’s not to say that it’s missing treble, or even the atmosphere around the instruments – it’s there – it’s just that if you’re expecting stratospheric extension your expectations may not be met. The Audio-Technica AT33Sa cartridge that’s installed on my Sota has frequency response spec’d to 50kHz – canine territory – that seems to extend upwards almost forever with grain-free resolution. The emphasis with the Spirit is more focused on the midrange, textures and meaty sonic mass.

As a very low compliance cartridge at 8×10-6cm/dyne, the Spirit works best with a very high-mass arm. The Karmadon Unipivot is such an appliance and worked well with the Spirit. Like any other arm/cartridge combination proper setup is key. Miyajima suggests a tracking force range for the Spirit at 2 – 4.5 grams with 3.5 grams recommended. In my kit, I found that 3.5g sounded a bit dark and syrupy, and incongruously, the treble seemed a little hot. Backing it off to 3g improved all of those issues and backing it off further to 2.75g proved to be the sweet spot. Textures became markedly richer with improved ambiance and overall detail was both enhanced and more smoothly delivered. The treble also calmed down appreciably. This cartridge definitely lives in the midrange, but when properly adjusted its delivery is very even across the frequency spectrum.

All of this was further improved with some well-spent time dialing in the arm, most critically getting the pivot ball as far down into the silicone as possible, accomplished by adjusting the knob that sits atop the cup. The further down the arm went into the silicone the smoother and more highly resolved the overall sound of the cartridge became, with the bass tightening and becoming punchier. As a bonus, the arm and cartridge seem to reject background noise better as increased damping is applied, certainly a good thing when spinning sixty-five-year-old records.

With the goo fully deployed it was a simple matter of using the setscrew on the tonearm base to raise and lower the entire assembly to fine tune the VTA. I tried using a microscope to approximate the elusive perfect 92-degrees but found that adjusted thus – or as close as I could get to it – the treble was still a little aggressive for my ears. Fiddling to your own taste, as always, is advised.

For comparison purposes, I’d previously had the Spirit installed on both the tin-armed Tech 12 and the Jelco arm on my Sota. The Karmadon arm worked better with this cartridge than either of the other two arms, with a larger more stable image and more refined, more colorful overall sound.

It Sounds Like Music

In combination, the Karmadon arm and Spirit cartridge deliver a large monaural image that is very, very stable, with instruments clearly delineated even as they’re layered over each other. The image is full enough to sound natural, and tall enough to achieve some sense of scale. It’s a believable reproduction of music.

In combination, the Karmadon arm and Spirit cartridge deliver a large monaural image that is very, very stable, with instruments clearly delineated even as they’re layered over each other. The image is full enough to sound natural, and tall enough to achieve some sense of scale. It’s a believable reproduction of music.

As already mentioned, in my system the arm and cartridge did an excellent job at reproducing bass. I’ve had a stereo AP copy of Sonny Rollins’ Way Out West (Analog Productions APJ 008) for years, but recently secured a mono first pressing (Contemporary C3530). Comparing the two pressings, the thing that struck me is how much more forceful the mono record sounds, despite a little persistent surface noise. Not only does Ray Brown’s bass have more weight, it has improved texture and definition as well. It sounds like wood and it’s much more prominent in the mix. By comparison, the stereo repress, while still a very good pressing, sounds a little reticent and flaccid. The stereo version also has terrible left-right panning of the instruments, somewhat out of character for an otherwise masterful Roy DuNann recording. The mono record is far more unified and is definitely the way to go with this one, especially with a fuller bottom end driving it all forward.

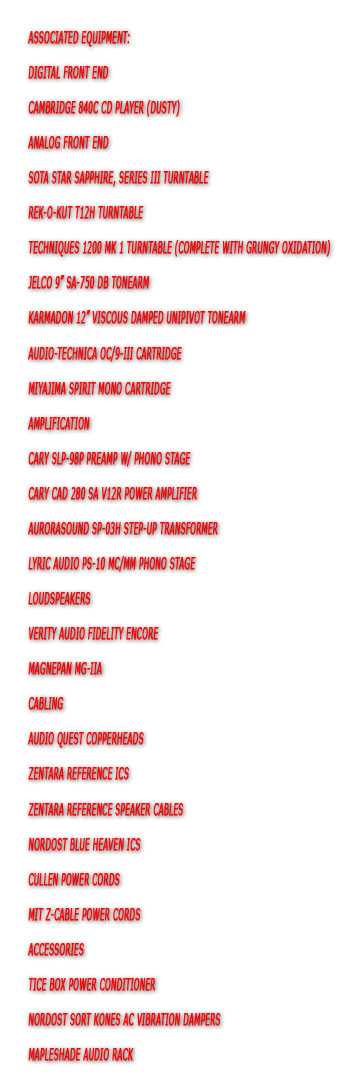

I’m fortunate to have an original Jazz West pressing of The Return of Art Pepper (JWLP-10), even if it has a few light audible scuffs and a generic sleeve (not an easy record to come by, even rough). It was beautifully recorded by John Kraus at Capital Studios in Los Angeles, and it really is among the highest examples of what’s often referred to as West-Coast cool. It’s also among one of the most evenly mixed recordings I know. The musicians are all blended with sonic egalitarianism, where everyone is clear and audible but no one is pushed out in front. It also has great clarity around all of the instruments. It’s a fantastic recording, with nothing buried or overly highlighted. The Karmadon/Spirit combo reproduces the recording with lively fidelity.

I’m fortunate to have an original Jazz West pressing of The Return of Art Pepper (JWLP-10), even if it has a few light audible scuffs and a generic sleeve (not an easy record to come by, even rough). It was beautifully recorded by John Kraus at Capital Studios in Los Angeles, and it really is among the highest examples of what’s often referred to as West-Coast cool. It’s also among one of the most evenly mixed recordings I know. The musicians are all blended with sonic egalitarianism, where everyone is clear and audible but no one is pushed out in front. It also has great clarity around all of the instruments. It’s a fantastic recording, with nothing buried or overly highlighted. The Karmadon/Spirit combo reproduces the recording with lively fidelity.

As a collector of 1950s and 60s era jazz records, I’d be remiss if I didn’t throw in a couple of Rudy Van Gelder recordings. In jazz there is no other engineer with a longer resume recording the best-of-the-best classic albums for Blue Note, Prestige, Savoy, Impulse, and other labels with that distinctive Van Gelder sound. Listen to them long enough and you’ll be able to pick out an RVG record a mile away, even on a recording you’ve never heard before.

Cannonball Adderley’s Something Else (BN-1595), which is really a Miles Davis record, is enormous – wide and tall – with good reverb around the musicians and bass that just throbs. My copy is an early second pressing (2nd pressing label on side one, 1st pressing label on side two) and it’s truly a great Van Gelder recording. Miles Davis’ unmuted horn has tight placement in the image but sounds life-size and right there. His tone captures his innate, soulful blues – skillfully polished, but with a slightly ragged, emotive edge. Miles’ immortal question at the end of “One For Daddy-O”, his gravel-voiced, ‘Is that what you wanted, Alfred?’ is easily answered: Hell yes! I can’t imagine that Alfred Lion would have disagreed, and he didn’t have the advantage of having this cartridge installed on his turntable.

Going further back in the Blue Note catalog is a ten-incher, The Gil Melle Quartet Featuring Lou Mecca, Volume III (BN-5054 Lexington) released in 1954. Melle, playing baritone, was among the first – if not the first – jazz artists to be commercially recorded by Rudy Van Gelder, who’d set up a recording studio in his parent’s living room in Hackensack, NJ. Alfred Lions liked the way Melle had been captured on tape and began using Van Gelder for all the Blue Note sessions, a relationship that lasted into the 1970s even after Lion had sold the label. The striking thing about this recording is that, despite its age and how early it falls in Van Gelder’s recording career, it’s got all the elements of what we think of as a classic RVG master: the crystalline capture of the horn, the clarity between the instruments, and the shear realism of the recording. Listening to this record, as opposed to something on Capital or Emarcy from the same period, it’s obvious how far ahead of his peers Van Gelder had gone in advancing state-of-the-art recording. The only possible difference between Volume III and a later recording like Something Else is that the soundstage is a little smaller, which may be a function of the record itself. Otherwise, everything you’d expect to hear in a Van Gelder record is captured on this sixty-four-year-old piece of Plastilite making the value of the Spirit cartridge riding in the Karmadon arm truly apparent: a true pre-stereo record with excellent recording quality that responds best to specialized equipment designed to retrieve that information. The Spirit cartridge picks up the sound while the Karmadon arm holds it rock steady. The combination reproduces the sound in those grooves with clarity, precision, and overall sonic excellence. I couldn’t have asked for anything more when I started putting this turntable together.

Going further back in the Blue Note catalog is a ten-incher, The Gil Melle Quartet Featuring Lou Mecca, Volume III (BN-5054 Lexington) released in 1954. Melle, playing baritone, was among the first – if not the first – jazz artists to be commercially recorded by Rudy Van Gelder, who’d set up a recording studio in his parent’s living room in Hackensack, NJ. Alfred Lions liked the way Melle had been captured on tape and began using Van Gelder for all the Blue Note sessions, a relationship that lasted into the 1970s even after Lion had sold the label. The striking thing about this recording is that, despite its age and how early it falls in Van Gelder’s recording career, it’s got all the elements of what we think of as a classic RVG master: the crystalline capture of the horn, the clarity between the instruments, and the shear realism of the recording. Listening to this record, as opposed to something on Capital or Emarcy from the same period, it’s obvious how far ahead of his peers Van Gelder had gone in advancing state-of-the-art recording. The only possible difference between Volume III and a later recording like Something Else is that the soundstage is a little smaller, which may be a function of the record itself. Otherwise, everything you’d expect to hear in a Van Gelder record is captured on this sixty-four-year-old piece of Plastilite making the value of the Spirit cartridge riding in the Karmadon arm truly apparent: a true pre-stereo record with excellent recording quality that responds best to specialized equipment designed to retrieve that information. The Spirit cartridge picks up the sound while the Karmadon arm holds it rock steady. The combination reproduces the sound in those grooves with clarity, precision, and overall sonic excellence. I couldn’t have asked for anything more when I started putting this turntable together.

Everyone looks to an arm and cartridge to faithfully reproduce what’s on their records. What’s harder to come by is a setup with an affinity for a specific type of recording. There are a lot of generalists out there, but that’s not always the best solution. Sometimes a more specialized setup is worth the effort, and monaural records are one of those specialties that definitely benefit from dedicated gear. The Spirit Mono was designed for this task and succeeds brilliantly, and the Karmadon arm, while it is actually wired for stereo, proves to be a fine match for the cartridge. In combination, they pull endless musicality from these old records.

Is This Hardware For Everyone?

Not necessarily, but then again, it might be right for you.

If you prefer the hyper detail of a cartridge like the Ortofon A90 (if you ever have the opportunity to hear one of these, definitely check it out), the Spirit Mono might not fill your bucket. It simply doesn’t deliver the kind treble extension or overall resolution that we’ve come to expect from truly state-of-the-art moving coils. Honestly though, I don’t believe it was designed to do that, and if you’re looking for that kind of extension or detail on old monaural recordings you may be barking up the wrong tree anyway.

On the other hand, if your record listening consists of a lot of old mono recordings a dedicated monaural cartridge is indispensable. The Miyajima Spirit Mono is a far better than average choice, handily besting the Ortofon 2M mono and Grado cartridges in dynamics, texture and drive, as well it should for it’s substantially higher asking price. If you’re ready to step up to a truly specialized cartridge with the capability to make those old records sound great, and if you’re expectations are for fantastic musicality over a state-of-the-art high-fidelity extravaganza, the Miyajima Spirit Mono should be on your short list. Properly set up it delivers more music than most people will ever hear out of those old records. It’s not the most modern hi-fi sound out there, but it’s not designed to play modern recordings, either. Within its intended field of operation everything about it just sounds right. Plus, I believe I already mentioned, it’s built like a tank.

The Karmadon Viscous Damped Unipivot arm is also going to appeal to a certain type of audiophile. Anyone can go out and buy a Rega RB-300. It’s a good arm, it’s easy to use, and they’ve sold a ton of them. But someone who wants an arm that’s out of the ordinary but also of very high quality might dig the Karmadon arms (any of them, really). Ordering an unheard tonearm from a far-away country does require a certain leap of faith, and this arm does require a little personal bravery to install, particularly soldering the wires, but with the right cartridge and attention to setup those efforts will be handsomely rewarded. Personally, I found the process quite satisfying, especially because with my limited skills it could have just as easily ended in tragedy (Here I am patting myself on the back again). It requires some work, but more importantly, it really delivered the sonic goods. Its stable, smooth delivery worked really well with the low compliance of the Spirit cartridge, and the ability to adjust the sound by changing the fluid damping characteristics is definitely useful. It doesn’t have the bells and whistles of some significantly more expensive arms, but it’s a stone-cold bargain at the asking price. You could spend a hell of a lot more money and not get as much arm.

In combination, the Karmadon Viscous Damped Unipivot tonearm and the Miyajima Spirit Mono cartridge deliver a great monaural listening experience in my room. This is a specialty setup, to be sure, but one that’s very worthwhile if you spend a lot of time with these old records. I’ve stated before: there are a million ways to get to great sound in this hobby. One of them is the pairing of the Karmadon Damped Unipivot Tonearm paired with the Miyajima Spirit Mono cartridge. Both highly recommended.

Postscript: And then it just sorta went away….

This is the fourth article I’ve written where I discussed this big old bastard of a turntable, and in all of them – at least the ones where it was running – I paid a good deal of attention to the speed instability issue. As I was doing my final preparations to submit this article something changed. I mentioned earlier that the wobble effect seemed to be lessening, but this evening – after running this thing for the better part of six months – I threw on two piano records: Meade Lux Lewis’ Yancy’s Last Ride (Down Home Records MGD-7. Down Home was a Norgran sub-label) and Mose Allison’s Local Color (Prestige 7121) and I was surprised and quite pleased with both of them. The wobble, the WOW, the piano vibrato has diminished almost to the point of irrelevancy. It’s still audible just a little bit on some of the longest sustained chords, like the big ones towards the end of Allison’s “Parchment Farm,” but nothing the average turntable listener would bother to complain about. The only thing I can think of is that over the past six months the weight of the motor weighed down the rubber grommets until they settled into a position where they just aren’t moving around any more. Or it could be something else altogether. Who knows?

I’m not complaining, mind you. I am, however, pulling out more piano records this evening.

Pax.

greg simmons

Specifications

Karmadon 12” Damped Unipivot Tonearm

Price: $420 US

Cast Magnesium Tonearm

1045 Steel Needle and Pivot Assembly

Spindle to Pivot Distance: 270mm

600k Silicone Damping Fluid

Cardas Internal Wiring

Miyajima Laboratories

Spirit Mono Phonograph Cartridge

Price: $995 US

Type: Moving Coil

Weight: 10g

Tracking Force: 2.0g to 4.5g (3.5 recommended)

Frequency Response: 20Hz to 23kHz (-3dB)

Impedance: 6 Ohms

Compliance: 8×10-6cm/dyne (10Hz)

Stylus: 0.4×0.7 mil bonded elliptical diamond

Stereo Times Masthead

Publisher/Founder

Clement Perry

Editor

Dave Thomas

Senior Editors

Frank Alles, Mike Girardi, Key Kim, Russell Lichter, Terry London, Moreno Mitchell, Paul Szabady, Bill Wells, Mike Wright, Stephen Yan, and Rob Dockery

Current Contributors

David Abramson, Tim Barrall, Dave Allison, Ron Cook, Lewis Dardick, Dan Secula, Don Shaulis, Greg Simmons, Eric Teh, Greg Voth, Richard Willie, Ed Van Winkle, and Rob Dockery

Music Reviewers:

Carlos Sanchez, John Jonczyk, John Sprung and Russell Lichter

Site Management Clement Perry

Ad Designer: Martin Perry

Be the first to comment on: Karmadon Viscous Damped Unipivot Tonearm and Miyajima Laboratories Spirit Mono Phono Cartridge