The Serinus Report

|

The Serinus Report |

| Music Reviews |

|

Jason Serinus |

|

10 October 2002 |

Lamento-Daniel Taylor, countertenor; Theatre of Early Music

[ATMA Baroque ACD2 2261]

Hearing the beauty and pathetic purity of Daniel Taylor’s countertenor as he enters to repeat, over and over, “Erbarm dich, erbarm dich, erbarm dich/Pity me/pity me/pity me,” his voice rising unannounced as from the ethers after an extended orchestral introduction, listeners’ hearts immediately open to his plight. This ability to touch a deep place within with the simplest of utterances is a rare gift indeed. And it is repeated over and over, not only in the aforementioned “Erbarm dich mein, o Herre Gott,” SWV 447 by Heinrich Schütz, but also in the six vocal selections that follow.

Hearing the beauty and pathetic purity of Daniel Taylor’s countertenor as he enters to repeat, over and over, “Erbarm dich, erbarm dich, erbarm dich/Pity me/pity me/pity me,” his voice rising unannounced as from the ethers after an extended orchestral introduction, listeners’ hearts immediately open to his plight. This ability to touch a deep place within with the simplest of utterances is a rare gift indeed. And it is repeated over and over, not only in the aforementioned “Erbarm dich mein, o Herre Gott,” SWV 447 by Heinrich Schütz, but also in the six vocal selections that follow.

Taylor’s production is not always flawless; he occasionally sounds a bit shaky when he adds emphasis to the voice during the lower lying passages of Dietrich Buxtehude’s beautiful “Wenn ich, Herr Jesu, habe dich” (BuxWV 107). As such, he is served best by the slow-moving music that occupies the bulk of Lamento. Regardless, the sheer beauty of the voice, and the clarity of diction, is rare indeed. And when Daniels moves higher in his range, soon after the start of Buxtehude’s “Klag-Lied” (BuxWV 76/2), the engaging beauty of the sound (far clearer than David Daniels’, if nowhere near as well managed in faster moving passages), and the depth of feeling, will leave most listeners deeply appreciative of his artistry.

The disc mixes vocal works by Schütz, Buxtehude, J.C. Bach, and Georg Melchior Hofmann with instrumental selections by Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (Lamento sopra la morte Ferdinandi III a tre) and Buxtehude (Mit Fried und Freud, (BuxWV 76/1). The longest work on the program is Philipp Heinrich Erlebach’s 14-miniute Sonata Terza in A major, with. All compositions date from the 17th and early 18th centuries. The recital ultimately tosses lamentation aside, ending with Buxtehude’s joyful 10-minute “Jubilate Domino” (BuxWV 64).

The Theater of Early Music, formed by Taylor, plays quite well, if lacking the excitement and crispness that such groups as the Academy of Ancient Music bring to similar repertoire. Sound is not ideally transparent, but is nonetheless quite acceptable. Warmly recommended.

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber: Unam Ceylum-John Holloway, violin; Aloysia Assenbaum, organ; Lars Ulrik Mortensen, harpsichord

[ECM (New Series) 1791 289 472 084-2]

Notable for their virtuosic demands and sudden changes of mood and tempo, Heinrich Biber’s eight violin sonatas of 1681 are considered the most forward-looking violin sonatas since those of Bach, Veracini and Schmelzer. Biber was one of the greatest violin virtuosos of the 17th century, who, like the violinist Ysaÿe and the pianist Liszt, wrote music that showcased his astounding playing technique. His music covers the entire range of notes available to violins of the period, offering all the possibilities for double-stopping and three- and four-note chord playing. What violinist Holloway justly terms Biber’s “dazzling” effects amount to a textbook of 17th century violin technique.

Notable for their virtuosic demands and sudden changes of mood and tempo, Heinrich Biber’s eight violin sonatas of 1681 are considered the most forward-looking violin sonatas since those of Bach, Veracini and Schmelzer. Biber was one of the greatest violin virtuosos of the 17th century, who, like the violinist Ysaÿe and the pianist Liszt, wrote music that showcased his astounding playing technique. His music covers the entire range of notes available to violins of the period, offering all the possibilities for double-stopping and three- and four-note chord playing. What violinist Holloway justly terms Biber’s “dazzling” effects amount to a textbook of 17th century violin technique.

Only in the hands of musicians who combine absolute technical mastery with abundant freedom of self-expression can the excitement and breadth of this music be fully expressed. Happily, the three ECM artists featured on this disc are more than up to the task. Violinist John Holloway founded the Baroque ensemble L’Ecole d’Orphée in 1975, which made the first complete recording of Handel’s instrumental chamber music on baroque instruments. Recipient of the 1991 Gramophone award for his recordings of Biber’s Mystery Sonatas and two Danish “Grammy” awards for his recordings of Buxtehude, he currently directs the Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra and is Professor of Violin and String Chamber-Music at the Hochschule für Musik in Dresden, Germany. His intensity and virtuosity bring to mind that of early music violinists Andrew Manze and Giuliano Carmignola, which says a lot.

Harpsichordist Lars Ulrik Mortensen received the “Danish Music Critics´ Award” in 1984; his three CDs of harpsichord music by Buxtehude earned him the title of “Danish Musician of the Year 2000” and received the 2001 Cannes Classical Award. Organist and composer Aloysia Assenbaum, married to Holloway, is former Head of the Music Conservatoire in Winterthur, Switzerland, where her series of “Portraits of Women Composers” earned her the 1995 “Equal Rights Prize” in Zurich.

The trio has previously released a much-lauded ECM recording of Viennese violin virtuoso Johann Heinrich Schmelzer’s 1664 Sonatae unarum fidium. In forthcoming live performances in Seattle, St. Paul, La Jolla, Tucson, Palo Alto, Berkeley, and San Francisco, they will perform works of Biber, Schmelzer, Pachelbel, Muffat, Froberger, and Bertali.

The recording at hand, released in the US on September 24, features four of Biber’s eight Violin Sonatas of 1681: III in F Major, IV in D Major, VI in C minor, and VII in G Major. The disc also includes two unpublished sonatas, 81 in A Major and 84 in E Major. A second disc of the remaining sonatas of 1681 is slated for future release.

Produced by Manfred Eicher, Grammy’s most deserving 2001 Classical Producer of the Year, the disc offers ECM’s accustomed atmospheric acoustic. In place of the intimate environment most conducive to this music, we hear a resonance that makes three instruments sound like the Choir of Westminster Cathedral. Nonetheless, the brilliance of the playing and the breadth of compositional mastery emerge in spades.

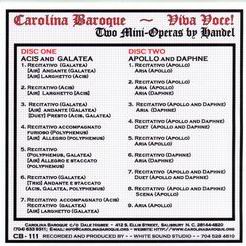

George Frideric Handel: Viva Voce!-Two Mini-Operas by Handel: Acis and Galatea-Apollo and Daphne Carolina Baroque, Dale Higbee Music Director; Teresa Radomski, soprano; Richard Heard, tenor; John Williams, bass-baritone-2 discs

[Carolina Baroque CB-111]

This home grown effort, recorded live in Wake Forest University’s Brendle Recital Hall on February 28, 2002, provides welcome evidence that baroque opera is alive and well in the land of Jesse Helms. The discs may not prove one’s first choice for these great works, but they provide enough fine singing and gratifying musicianship to deserve sincere applause.

This home grown effort, recorded live in Wake Forest University’s Brendle Recital Hall on February 28, 2002, provides welcome evidence that baroque opera is alive and well in the land of Jesse Helms. The discs may not prove one’s first choice for these great works, but they provide enough fine singing and gratifying musicianship to deserve sincere applause.

Carolina Baroque, organized by Dale Higbee in 1988 to perform Baroque music on period instruments, has performed throughout the Southeast and on public television. Both soprano Radomski and tenor Heard are on the faculty of Wake Forest University, while bass-baritone Williams, a regional winner of the Metropolitan Opera Auditions, performs locally as well as throughout the Europe and the US. Many of the instrumentalists hold impressive credentials.

Acis and Galatea is abridged; the opening Sinfonia, all choruses, Acis’ “His hideous love/Love sounds the alarm,” Galatea and the chorus’ “Must I my Acis still bemoan?” and the countertenor role of Damon are all eliminated. (Choruses were sung by the soloists in the 1718 premiere). Also eliminated are 1718’s two oboes, one of which doubled flute and recorder. Apollo and Daphne is presented in full, save for bassoons and oboes.

One drawback is that the recording is released on limited fidelity CD-Rs. The soundstage is narrow, the acoustic overly reverberant, with some distortion on high notes and a low electronic hum evident throughout; the sound simply cannot compare to Dorian’s competitive releases of these works. In addition, Williams has a much bigger voice than the other soloists, necessitating volume adjustment. Regardless, the musicianship is quite fine. Williams’ “Ruddier than a Cherry” lacks the subtlety and humor of David van Asch’s for The Scholars of London, but his “I rage” sounds more convincing. Radomski too lacks the nuance of the Scholars’ Kym Amps as Galatea, but there is much beauty, if not ideal flexibility, in her upper range.

Strangely, while Radomski and Williams sing Acis in “operatic English,” the fine voiced Heard sings in straight ahead Americanese. No such problem in Apollo, performed in Italian. When comparing this performance with Dorians’ forces, Bernard Labadie’s Les Violons du Roy and soloists Karina Gauvin and Russell Braun (Dorian) impress as in a class all their own. Absent is the refined charm, nuance, and sonic transparency they offer in Dafne’s elegant “Felicissima quest’alma, ch’ama sol la libertà” and throughout their generously filled disc.

Tchaikovsky – Britten – String Quartets -The Brodsky Quartet

[Challenge Classics CC 72106]

Here’s an opportunity to explore two “first quartets” plus three Divertimenti by two great composers who shared a common “outlaw” orientation: one, Pyotr Iliych Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), remained tortured by his closeted homosexuality throughout his life: the other, Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), transcended societal criticism and threats of repression to eventually achieve worldwide recognition for his lifelong relationship with tenor Peter Pears, for whom he wrote much of his vocal music.

Here’s an opportunity to explore two “first quartets” plus three Divertimenti by two great composers who shared a common “outlaw” orientation: one, Pyotr Iliych Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), remained tortured by his closeted homosexuality throughout his life: the other, Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), transcended societal criticism and threats of repression to eventually achieve worldwide recognition for his lifelong relationship with tenor Peter Pears, for whom he wrote much of his vocal music.

According to the disc’s liner notes, just twenty years after Tchaikovksy’s death, the great Russian impresario Diaghilev wrote in Paris: “Tchaikovsky thought of committing suicide for fear of being discovered a homosexual; but today, if you are a composer and not a homosexual, you might as well put a bullet through your head.” That, of course, was a major exaggeration; the mass suicide of 20th century heterosexual composers never took place. But it is hardly stretching the point to note that Tchaikovsky’s guilt over his homosexuality (referred to as ‘Z’ in his correspondence) infused his writing with a deep appreciation of lyrical beauty and, at times, a wrenching emotional torment.

Tchaikovsky composed his justly loved String Quartet No. 1 in D major, Op. 11 in 1871, three years after a mixed reception to his First Symphony left him on the edge of a nervous breakdown. The extended first movement (here 12’13) overflows with lyrical melody, ending with a climax so complete and affirmative that the work could stand by itself. Then comes the famous Andante cantabile (7’30), based on the folksong “Sidel Vanya” Tchaikovsky had collected from a local carpenter two years before; this movement became so popular throughout the world that it led Leo Tolstoy to openly weep during a public performance, and caused the composer to exclaim “they don’t want to hear anything else!” The Scherzo is quite fiery, the Allegro Giusto Finale bursting with joy. Simply put, this is one of the most melodically accessible and ingratiating string quartets in the repertoire.

Listening to the Brodsky’s very direct, cleanly recorded performance, one may wonder what qualities in Tchaikovsky’s second movement caused Tolstoy to weep and Europe to become obsessed with the work. One has only to turn to the St. Lawrence String Quartet’s 2001 release of Tchaikovsky’s String Quartets No. 1 and 3[EMI Classics 7243 5 57144 2 8] for a performance that tugs at the heart. St. Lawrence’s Andante cantabile may only be 11 seconds slower, but the warmer acoustic (too soft and reverberant, but offering as welcome compensation far greater prominence to the cello) and more deeply felt playing successfully conveys the music’s emotional core. Some of St. Lawrence’s other movements, including a faster Finale, are equally successful.

The Brodsky’s direct approach, which works so well in 20th century music, succeeds admirably in the Britten. The String Quartet No. 1 in D major, Op. 25 (1941), with its Bergian influence and engaging rhythms, comes to life. So does the youthful Three Divertimenti (1936), whose March, Waltz, and Burlesque are revised from parts of an original Suite Alla Quartetto Serioso (1933) that bore the subtitle “Go play, boy, play.” This is wonderful music; give it the quiet and concentration it deserves, and your life will be all the better for having listened.

Renée Fleming: Bel Canto-Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Patrick Summers conductor

[Decca 289 467 101-2]

If any recital could establish soprano Renée Fleming as substantially more than a gorgeous woman with a beautiful voice sometimes employed without interpretive insight, this generous, Billboard Chart-topping disc of well loved and lesser-known bel canto scenes by Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini will certainly do the trick. Playing it through, it is clear that Fleming possesses the vocal and emotional range, flexibility, and timbre required to give life to the high-flying femmes who dominated early 19th century Italian repertoire.

If any recital could establish soprano Renée Fleming as substantially more than a gorgeous woman with a beautiful voice sometimes employed without interpretive insight, this generous, Billboard Chart-topping disc of well loved and lesser-known bel canto scenes by Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini will certainly do the trick. Playing it through, it is clear that Fleming possesses the vocal and emotional range, flexibility, and timbre required to give life to the high-flying femmes who dominated early 19th century Italian repertoire.

In singing bel canto, Fleming returns to her roots. The soprano made her professional debut in 1986, not in the lyric roles of Mozart or Strauss, but as the coloratura Konstanze in Salzburg’s Landsestheater production of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Though many lyric soprano debuts followed, Fleming’s bel canto performances have continued through autumn 2002 Paris and Metropolitan Opera appearances in Bellini’s Il pirata.

Fleming offers far more than beautiful singing. A case in point is the final sleepwalking scene and uncharacteristically happy conclusion to Vincenzo Bellini’s La sonnambula. The voice, tinged with pathos, immediately impresses with the gravity and weight of Amina’s sorrowful plight. The entire grab bag of coloratura technique, including grace notes, roulades, trills, and endless variations, seems at the soprano’s disposal. And as Amina awakens from sleep to find herself surrounded by villagers and her fiancé rejoicing in her innocence, her vocal color convincingly shifts from pathos to joy.

Are comparisons to recorded performances of the greatest coloraturas of the last 50 years in order? Certainly Fleming paves the way. In her own liner notes for the album, the artist states:

When I first started to study singing, I was under the impression that the style of singing and the repertoire we refer to as bel canto was at the centre of every artist’s repertoire. This was due to the fact that great singers of the day, Maria Callas, Joan Sutherland, Montserrat Caballé, and Beverly Sills, revived this repertoire and made it central to their careers… Bel canto style still represents for me the culmination of all the elements of great singing.

She then throws down the gauntlet by continuing:

When Callas, Sutherland, Caballé and Sills began reviving these operas, they were extensively cut, damaging continuity and undermining the larger musical conception… Work on original material has shed much light … on how individual vocal lines should be ornamented, and on how that ornamentation differs from composer to composer. On this recording, the performance practice was deeply influenced by the pioneering work of Dr Philip Gossett, who composed much of the ornamentation of the vocal line.

[As one example}, the highly ornamented version of the cabaletta [“Ah! Non giunge” from La sonnambula] which is printed in most current editions was actually added to the score by an unknown hand. The original manuscript demonstrates that Bellini wrote a much less florid melody, which should only be ornamented when repeated…

What do the results of this scholarly collaboration sound like? The lyrical “Ah! non credea mirarti” emerges so sweetened with high-lying ornaments as to undermine the fundamental pathos of Amina’s predicament; the cabaletta’s execution, albeit faithful to Bellini’s writing, nonetheless lacks the sheer brilliance of Sutherland or the weight of Callas. In fact, time and again, as one compares performances by these singers and the others Fleming mentions, one senses that conductor Summers intentionally holds back in the orchestral climaxes because Fleming’s voice cannot emit blazing final notes capable of cutting through instruments going full blast.

But that’s just one performance. When we turn to “D’amor al dolce impero” from Rossini’s Armida, we discover truly revelatory singing. Caballé recorded this tour de force on her early Rossini Rarities disc, while Callas left live documents of her 1952 Florence May Festival and 1954 San Remo performances. Both older sopranos sing with unmatchable force and forward momentum, Callas in 1952 literally leaves mouths agape with interpolated Ds, thrilling runs, and a blazing high F conclusion that no other singer in her right mind would ever dare attempt. (Callas dropped these variations just two years later). Caballé too is thrilling, if incapable of rising above a high C. But the sorceress Armida begins singing “Nature always submits to the gentle commands of love,” not to knock our socks off, but rather to enchant Rinaldo into exchanging his weapons for the garlands of love. Here, Fleming succeeds. Only in her voice do we find flirtation, charm and smiling tone. She does at one point sound a bit more like Blanche Dubois than Armida, but then again, Callas basically sounds like a bitch on wheels. Fleming’s is a performance to listen to again and again.

As for the other scenes on the disc, Fleming’s “Bel raggio lusinghier …Dolce pensiero” from Rossini’s Semiramide cannot approach the brilliance of either Sutherland or Callas, but it’s an absolute success in its own right. The final scene from Bellini’s Il pirata, a Callas specialty, lacks the weight and authority La Divina brought to this music, but it is sung with far more freedom and ornamentation than Callas could offer later in her career. The final scene from Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia, the very music in which Caballé made her unscheduled 1965 American debut, is not of the show-stopper variety, but nonetheless impresses. As for the joyful scena from Donizetti’sMaria Padilla, Fleming’s vocalism is so lovely and brimming with health that all one can do is be thankful for her many gifts, and hope for the opportunity to hear her perform the music live.

Leontyne Price Rediscovered-Carnegie Hall Recital Debut [RCA 09026-63908-2]

The great American soprano Leontyne Price was 38 and at the height of her powers when, on February 28, 1965, she made her Carnegie Hall recital debut. Both the rehearsals and the 29-selection recital (including four operatic encores) were recorded. Yet only two arias were ever previously released, and those received limited circulation.

The great American soprano Leontyne Price was 38 and at the height of her powers when, on February 28, 1965, she made her Carnegie Hall recital debut. Both the rehearsals and the 29-selection recital (including four operatic encores) were recorded. Yet only two arias were ever previously released, and those received limited circulation.

Though liner notes suggest that the document was inexplicably overlooked, part of the reason may lie with the recording itself, which lacks the technical sophistication of Price’s earlier Living Stereo efforts. The piano is situated on the left, Ms. Price on the right, as though divided by the Mason-Dixon line; both are denied sufficient resonance and liquidity to allow them to shine at their best.

Ms. Price also sounds a bit husky at times, not only in her usual place at the bottom of the range, but also farther up. The reason probably lies in her grueling schedule; the recital was sandwiched amidst three Aidas, five Cosis, and five Ernanis. (Ms. Price later trimmed her performance schedule in an attempt to preserve her instrument). Nonetheless, in repertoire appropriate to her gifts and temperament, her voice shimmers, the sensual vibrato and ravishing high notes for which she remains prized delivered in spades. Apart from a few weakly hit high Cs, Price supplies sufficient stellar vocalism to justify midnight runs to Tower.

The soprano begins with Handel; after a beautifully voiced, albeit unornamented “Care selve” (almost as exquisitely poised as her commercial recording), she assays arias from Agrippina and Julius Caesar. While Price sang Cleopatra as early as 1956 (Arkadia GI 803.1), she could never offer the flexibility, focus, and heart-touching temperament that Sills, Swenson and others have brought to the role.

Then come eight of Brahms’ Zigeunerlieder (Gypsy Songs). As an operatic gypsy, Price excelled in Carmen; here, however, her operatic grandeur and poor German diction ill serve the repertoire.

The soprano returns triumphant with a tremendous, note-perfect “La mamma morta” from Giordano’s Andrea Chénier. This is echt Price, with all the forward momentum, high drama, and shimmering highs that lead us to forgive her occasional excesses and lapses of taste.

Songs by three 20th century composers, Poulenc, Barber (who championed Ms. Price early on), and Hoiby, are followed by four Spirituals. There are lovely moments here and there, as well as occasional yelps and awkward transitions; the impression that Ms. Price’s forte lies with opera remains unchallenged.

Between encores at one of Price’s late San Francisco recitals, an impassioned audience member shouted out “Sock it to us, Leontyne.” Ms. Price does that and more in encores from La rondine, Porgy and Bess, Adriana Lecouvreur, and Tosca. Although she emphasizes punch over finesse, occasionally rushing phrases, she emits sounds so incomparably sensual and thrilling that her vocal uniqueness remains unassailable.

![]()

Don’t forget to bookmark us! (CTRL-SHFT-D)

Stereo Times Masthead

Publisher/Founder

Clement Perry

Editor

Dave Thomas

Senior Editors

Frank Alles, Mike Girardi, Key Kim, Russell Lichter, Terry London, Moreno Mitchell, Paul Szabady, Bill Wells, Mike Wright, Stephen Yan, and Rob Dockery

Current Contributors

David Abramson, Tim Barrall, Dave Allison, Ron Cook, Lewis Dardick, Dan Secula, Don Shaulis, Greg Simmons, Eric Teh, Greg Voth, Richard Willie, Ed Van Winkle, and Rob Dockery

Music Reviewers:

Carlos Sanchez, John Jonczyk, John Sprung and Russell Lichter

Site Management Clement Perry

Ad Designer: Martin Perry

Be the first to comment on: The Serinus Report